Beautiful Invasions, Part 2: The Generalized Invasion Curve

Reading about scotch broom as I drove away from my wedding was the first time I explicitly remember being able to identify an invasive plant, though I don’t remember wondering what the term meant, so I must have heard it somewhere before. Himalayan blackberry was the next I became intimately familiar with, after buying a few acres and more than a few blackberry patches in the summer of 2020. In King County, the most populous county in Washington state, and the one where Seattle is located, Himalayan blackberries are classified as a class C noxious weed, along with dozens of other species. Noxious weeds are

non-native plants that, once established, are highly destructive, competitive and difficult to control. They have economic and ecological impacts and are very difficult to manage once they get established. Some are toxic or a public health threat to humans and animals, others destroy native and beneficial plant communities.

To be Class C just means that they are so widespread that control is effectively impossible and therefore not required. It’s a surrender, an acknowledgement that humans are not capable of modifying a landscape in any way they see fit after all, at least not without effort or expense beyond what would be gained. Earlier in a plant’s uninvited spread throughout the region, before it becomes Class C and when control or eradication is still possible, attempts must be made. The county says so, but either can’t or doesn’t do much to enforce this. Private landowners are responsible on their own land for removing these invaders that haven’t yet completed their invasion, and counties, cities, and nonprofit organizations will often do so on public lands, bringing their own work crews or rounding up volunteers to participate. Where I live, while we aren’t required to pull blackberries, we must still remove knapweed, milk thistle, gorse. There are others — pages and pages of others.

Not so once a plant is Class C — recommendations about when to control these typically revolve around the impact the offending plant is having on the function of the land, or any economic impact. Said another way: remove it if there’s a tangible cost to not doing so, otherwise don’t bother trying. That economic impacts are so regularly cited when it comes to invasive species is telling, though not surprising. Anyone who pays attention to human nature knows that financial profit will motivate behavior far more readily than anything so soft around the edges as ethics or inherent goodness, even where such a thing can be agreed upon. It’s expensive to remove invasive species. This goes beyond just physical labor: tools, transportation, chemicals, scientists to study impacts, not to mention the bureaucrats who need to either mobilize the efforts or be worked around. So it’s no surprise that municipalities and private homeowners are unenthusiastic about putting in the often herculean and ongoing effort that must go into eradication without being sure that the effort will pay its dividends. It can take more than 500 hours to clear an acre of a well established blackberry stand. And those dividends are most appreciated if they come back the way they went out: financially, not as biodiversity or warm and fuzzy feelings about having restored an ecosystem.

There is significant overlap between “noxious weeds” and invasive species, but the overlap is not complete — to be noxious just means that something has been legally classified as invasive. That something hasn’t been legally classified as such doesn’t mean it’s not invasive. According to the Weed Science Society of America, noxious weeds “often lack natural enemies to curtail their growth — enabling them to overrun native plants and ecosystems.” The idea of the class C ones, the ones too far gone to bother trying, seems fatalistic at first glance, but is based in science (and economics, which as we’ve established, drives the science we do more often than not).

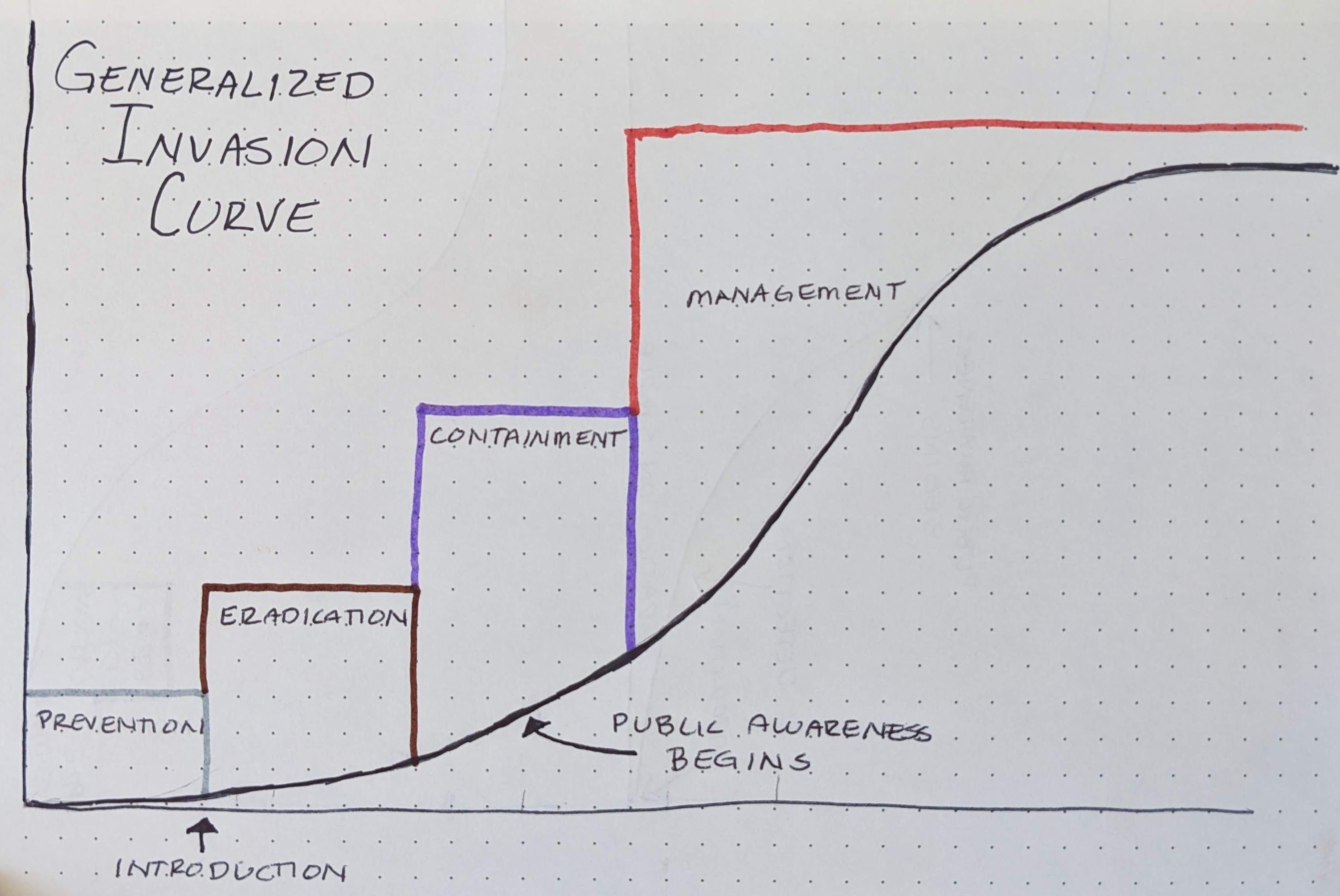

The generalized invasion curve is a tool for understanding the phases of an invasion, and the relative costs (and likelihood) of management.

The first phase is prevention. This is the most cost-effective option, though difficult in the way problems that haven’t become problems yet are: it can be hard to convince people to pour time and money into something that may or may not ever happen, when success looks like, indeed, nothing happening. It also turns out that in areas that are not yet invaded at all, the best way to ensure that they stay that way is to keep humans out entirely. This is both because humans are the most common way that invaders first arrive somewhere, but also because, left to their own devices and undisturbed, native ecosystems are relatively good at preserving themselves. Unfortunately, if humans are bad at anything, it’s solving problems by not doing something, not to mention that there are not many places left in the world where people cannot be found.

The next phase on the generalized invasion curve is eradication: this phase doesn’t often last long, but there is a window of opportunity when something is first introduced and shows signs of becoming invasive to root out the problem before it becomes intractable. The eradication must be complete. If that fails, next is containment — not trying to remove it from where it is, but trying to prevent it from spreading further. At least in Washington state, each county has its own Noxious Weed Control Board that maintains different lists of what is defined as class A, B, and C. While there is overlap, there are some things we’ve surrendered to in some parts of the state, which still require control in others. We can succeed at containment, for a time.

Containment is the penultimate phase and is when public awareness of the problem generally starts: success in the earlier phases is something few people are aware of, for reward-driven humans, the potential for reward here is low. We’re not good at not doing things, and we don’t congratulate people when something doesn’t happen, even if these are the harder tasks. And when containment fails? From there it’s resource protection and management: remove it from economically high-value areas where it’s feasible, let the rest go. It’s too late.

Human records being imperfect, and relatively skewed toward recency, there are some species we’re just not sure about. Bracken fern, for example, is prolific in my own backyard as it is around the world, found on every continent except Antarctica. It is tall, up to five feet, but unlike most evergreen ferns in the Pacific Northwest, is a perennial, dying back in the winter to reemerge in the spring, its fiddleheads distinctive and the subject of much debate regarding their edibility and carcinogenic properties. (They are frequently consumed in Japan and Korea, where indeed, the incidence of stomach and throat cancers is higher, but the carcinogenic compound found in them is readily degraded by both water and heat, making it actually quite safe to eat when it is both cooked and used in moderation). It’s also frequently derided by gardeners, for its tendency to pop up anywhere and spread, and the notorious difficulty of eradicating it.

The common name for pteridium aquilinum is, depending on who you ask both “Western bracken fern” and “Eastern bracken fern.” Attempting to ascertain the native range of this plant, scientists in Europe, Asia, and North America all claim its native range. Native everywhere, and therefore, native nowhere? The University of Puget Sound concedes: “It presumably evolved in a single region and then spread very effectively elsewhere.” This feels obvious, if you think about it carefully: the idea that the exact same species would spontaneously evolve around the world is a bit preposterous: of course it first emerged somewhere and then spread outward.

This reveals something about human nature, perhaps: if a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? If a plant spreads and no one makes a record of it, was it always there? This habit of defaulting to “native” when there’s no record of the contrary is something Dr. James Carlton takes issue with too. An invasion biologist, Dr. Carlton is particularly well known for his work on bringing to the forefront the idea of invasions via ballast — ballast is water placed in the hold of ships to help them maintain their weight and balance when they’re not carrying cargo. This ballast water is then released into port upon arrival, since cargo will do its job on the return trip. This release includes every living thing that was in the water when it was first taken in, a prime invasion opportunity. Dr. Carlton was the first to apply the term “cryptogenic” to things currently living: in paleontology, a cryptogenic species is one that has a fossil record without any such record for earlier versions, meaning its evolutionary history is unknown. When used to describe living things, it’s an admission that while we know something currently lives in an ecosystem, we don’t know whether it’s native or introduced. Dr. Carlton argues that this, instead of native, should be the default until it can be proven one way or the other.

It does complicate things a bit: if something is not clearly invasive, which requires some level of harm, and nor is it necessarily invasive, then what to make of our previously clean dichotomy? But of course many things are neither — not native, but humming along, not invading either. Ecosystems are complex webs of interdependence and relationships we largely don’t understand, clean dichotomies are few.

Educational resources abound for how to remove invasive species. Counties and states and agricultural extension offices maintain lists and provide training. In February 2022, I attended a virtual version of Washington State University’s annual “Winter Forest school.” There were 29 different sessions you could attend, many of them duplicated across Eastern and Western Washington — there was a “Forest Health in Eastern Washington,” and its Western Washington counterpart. There was also an “Invasive Weeds” session for each geography — these were the only two sessions that had the word “invasive” in their title or description, but they were far from the only ones covering the topic. The forest health sessions discussed it. The sessions on managing a forest for songbirds discussed it, as did those on climate change and wildfires.

I’ve attended probably a dozen such training sessions on invasive species now, most of which were unintentional after the first couple, having been fooled by a title suggesting a different topic. Most of them are pretty much the same: they tell you what invasive species are and why they are bad (economic and biodiversity impacts). They tell you what the invasive species are in your area and how to identify them. They tell you what your options are for removing them. In broad strokes, the options for removal are typically:

- Cut it down, if it’s a tree and the roots are too big to be dug out. This probably won’t work unless you also apply a stump and vine poison to the stump, and even then you’ll probably need to go back for a few years to re-treat.

- Pull it out by the roots. Make sure you get it all though, because a lot of these plants will actually just grow back more robustly than they were before, as though trying to take vengeance for the scarring you’ve done to their roots. Plants don’t feel vengeance, but they make you think they might.

- Just mow it all down. Repeat 2–3 times a year for three to four years. Maybe more. It’ll die eventually, along with everything else you’re mowing down.

- Apply herbicides

- All of the above

- Repeat

The trainers offer some guidance on how to choose between or among these methods. Don’t choose herbicides if you’re planning to use the land for agriculture. Don’t choose mowing if the invasive species are interspersed with native ones that you want to let be — the removal of invasives is more likely to be successful if something else remains growing there. Bare land doesn’t stay bare for long: something grows back or it washes away.

What the training sessions don’t, for the most part, talk about, is when or how quickly to remove invasive plants: if invasive plants are a universal bad, then removing them is an unequivocal good. So of course, the answer to the question of how quickly they should be removed, by omission of an answer, is assumed to be: now, as fast as you can.

Sources

Burdick, Alan. Out of Eden: An Odyssey of Ecological Invasion (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2005)

By Willow - Own work, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2318774

Invasive Species Centre, Invasive Species and Stages of Management: Investing in Prevention

King County, WA, Noxious Weeds

Slater Museum of Natural History, University of Puget Sound, Bracken Fern

Soll, Jonathan, Controlling Himalayan Blackberry in the Pacific Northwest, (The Nature Conservancy, 2004)

St. George, Zach, The Journeys of Trees: A Story about Forests, People, and the Future (W. W. Norton Company, 2020)

Weed Science Society of America, Fact Sheet: Do you have a weed, noxious weed, invasive weed or “superweed”? (2016)